Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII, 1966 (Picture credits to Tate Modern)

Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII, 1966 (Picture credits to Tate Modern)

The Equivalent VIII (The Bricks) by Carl Andre, acquired by Tate Modern in 1972, has been causing anxiety on communication between the museum and the general audiences, which continues to challenge Tate Modern’s interpretation strategy over the past decade. This is due to the fact that Conceptual Art, since the emergence of Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 work Fountain has remained mind-boggling to audiences in general.

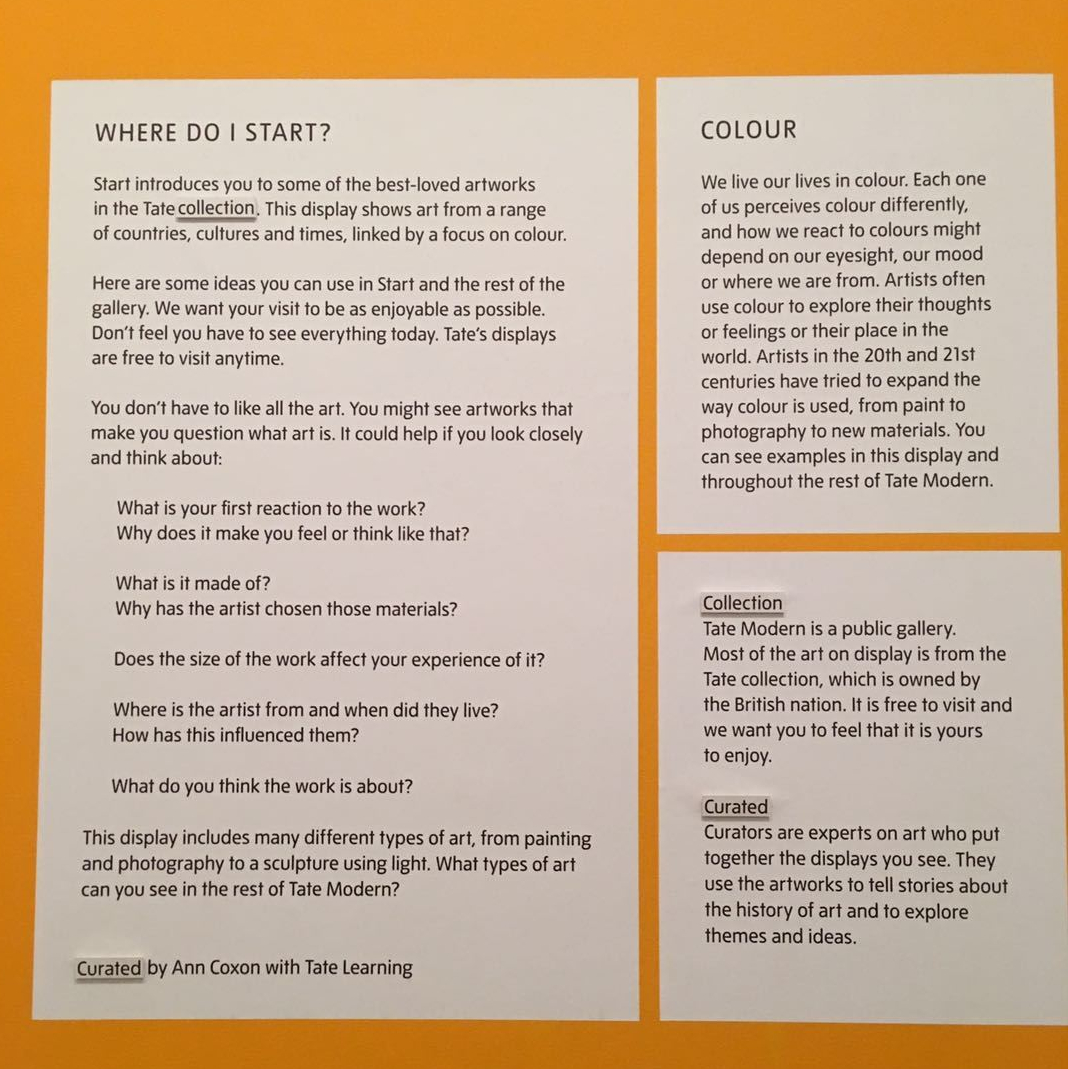

Tate Modern has been strategically displaying the iconic conceptual sculptures from its collection for learning purpose. However, there is dissonance between the purpose and the methods. For example, the display room of ‘Explore Materials and Objects’ features the work Fountain 1917 by Marcel Duchamp as well as other conceptual sculptures, presents raw materials juxtaposed with artworks and encourages visitors to touch the substances. While a particular gallery highlights the learning theme, the gallery itself nurture the premised cognition that every work is legitimate being there as art, distinct from an object or material. Meanwhile, the wall text interpreting the works following the reversed logic of art creation, as in to encourage audiences to explore the reason why an artist chooses a particular material could justify the idea and the work being art. Thus, a visitor may well ask why this particular idea and work has a significance to be an artwork and how it is relevant to themselves.

The dissonance is probably caused by the display room, the ‘white cube’, a term theorized by Brian O’Doherty. The ‘white cube’, in a modern and contemporary art museum is the core container for artworks, which conceived as a place of aesthetic, free of context, and out of daily life. However, the separation between artworks and everyday life could result in cognitive gap that interferes the visitor learning experience, especially on conceptual art. In other words, once a piece of artwork is well displayed in a gallery, it is presupposed as an established artwork rather than an ordinary object or a pile of materials. When we go back to Carl Andre’s conceptual art, it is well explained by himself:

‘Works of art don’t mean anything, they are realities. What does reality mean? It’s there. Because our culture tends to turn everything into language, We lose sight of the actual being of things.’ (From Tate Shots)

In other words, Carl Andre’s concept is to make people realize the ‘physical reality’ that around us instead of the artistic or linguistic projection of reality. Thus, the better idea to communicate with audiences with this work should be bringing the object/material nature to them, to have them encounter the artwork as it originally is: an object or a pile of material.

This idea is based on a visitor-centered curation strategy, informed by the museology theory of Edu-curation (Pat Villeneuve, Ann Rowson Love) and the Constructivism Learning Theory (Hein and Hopper-Greenhill). Simply put, change the artwork-centered space to visitor-centered space. Further, by moving out the conceptual sculpture from gallery room to the non-gallery space throughout the Tate Modern’s building, we could possibly deconstruct the premise for a conceptual artwork being art, facilitate a personal experience-based visitor engagement, and then invite visitors to question the significance of ideas in conceptual arts.

For a visitor-centered purpose, those meaningful questions could be brought up into a discussion: Why a particular object catches their attention and how does it matter to one’s life? Whether it being art or not causes a difference in their mind when they encounter it? How the idea expressed by the artist is relevant to you?

etc.. In the whole visiting experience, the most important thing is not about the position or definition of an artwork, but how seeing art or not-seeing art feels differently to an individual.

*This exploration, however, brings me another question: the contradictions between the conservation of conceptual art and the dematerialized nature of conceptual art. Sometimes it seems that what the museum preserves are the art that is dead or conceptually changed. So the interpretation could be really tricky, it seems like the museums should firstly admit ‘this art is not an art’ before taking visitors through the concept behind and go back to the meaning why the museums buy art that denies itself to be art.

Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII, 1966 (Picture credits to Tate Modern)

Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII, 1966 (Picture credits to Tate Modern)